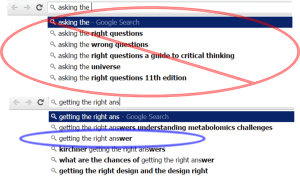

There has been more than one piece written about asking the right questions. I do not disagree that this is important. But stepping back for a moment, what is the real objective? It’s getting the right answers.

To get the right answers, it does not involve asking some of the right questions, it involves asking ALL of the right questions. Of course, this is not be confused with getting the right answers to the wrong questions (problems that can occur in surveys). Since life does not occur in a lab or static environment, there is almost never an official list of the right questions to ask. Usually, it’s the answers to certain questions which then help develop additional inquiries. Much like an excel sheet with circular references, it’s an iterative process.

If you have paid attention to the water crisis in Flint, MI, it should be apparent (regardless of any biases), that somewhere along the lines, people were not getting the right answers. While it might be an interesting exercise to review all the breakdowns in this tragedy, I believe the facts are still being discovered, so I’ll save that for another day. Instead, I would like to focus on a successful outcome.

Case study:

A livestock company needed to consolidate two processing facilities (each in separate states, over 200 miles apart) into one operation at the corporate headquarters. The savings to be realized were absolutely critical to the long-term health of the organization. The management team had developed a comprehensive plan to transition operations without losing any growing or processing capacity. The issue with this plan was that the company did not have the significant capital it needed after a sharp jump in commodity prices.

The right answer ended up being a “rip off the bandage” approach. The facility consolidation was accelerated greatly, reducing the timeline from more than one year down to less than 3 months. The capital requirements were reduced by over 75%, saving many millions of dollars.

The original plan identified all the major risks and incorporated safeguards to effectively eliminate those risks. However, the final consolidation plan, which was very successful, was made by accepting risks. The trade-off was essentially taking risks (listed below) in order to start realizing savings within 2-3 months that would then provide the cash flow to fund a reduced set of capital projects within the first year. Some of the key changes included:

- Lower capacity – The company accepted a temporary reduction in growing capacity of up to 18%. This was not an insignificant number. Most companies could not afford to put 15-20% of their revenue stream for their core business at risk due to a supply disruption. This risk was to be mitigated by three factors: 1) relying on excess inventory to cover part of the shortfall; 2) eliminating marginal customers, thus decreasing the growing capacity that needed to be replaced; and 3) if necessary, redeploying the immediate savings as incentives to help expand growing capacity.

- Risk Management – The revised plan postponed the timing of a sprinkler system installation until after the consolidation was complete. Obviously, a fire in the newly consolidated facility would have been devastating, but by changing this assumption and timeframe, along with the temporarily lower capacity, this reduced the size and scope of the project and would allow the new system to be financed out of operational savings within the year. This was a trade-off in taking a high-dollar low-percentage risk and generating significant cash flow vs. being completely risk averse and postponing consolidation savings.

- Focus on bare necessities – There were other capital projects that were needed for the company to operate with a high level of efficiency, which were re-classified as “nice to have.” While they were ultimately kept in the plan, the timing was adjusted so that they would be self-financed through savings. In the meantime, the company would have to make due.

In conclusion, since the company would begin reaping the consolidation savings within the next quarter, they were able to self-finance the deferred capital spending and, if needed, provide incentives for contract growers to expand capacity to meet their needs. More importantly, the distraction of this project to the company was severely reduced. Instead of having this hang over everyone’s heads for a year plus, the heavy lifting was done within two months and most personnel were back to “business as usual.” Only a small team was required to handle the remaining asset disposition and facility closing.

In getting to the right answers, there were many rounds of questions asked over 6-8 weeks which were answered with a significant amount of analysis. By analyzing the customer profitability in detail, the prospect of reducing growing capacity was confirmed as a viable option. Once this was on the table, the rest of the project was re-assessed in a completely different light. In the end, a team that worked tirelessly, was able to turn the year 1 cash flow on this project from a deficit of almost $6.0 million to a positive cash flow of $0.75 million.